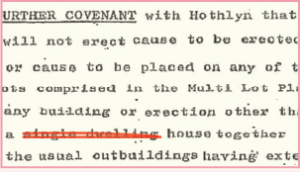

Restrictive covenants have long been registered on land titles as a means of controlling land use and development. Some of the most common covenants applicants seek to remove (or vary), are ‘single dwelling’ restrictions that prohibit development of land with more than one dwelling.

Regular readers and practitioners will be aware that there are three primary means of removing or varying a restrictive covenant. The three methods are via;

- A planning permit application;

- A Supreme Court application, or;

- A planning scheme amendment.

Each of these three methods is subject to different assessment criteria and has its own pros and cons. The most appropriate method to use will only be known once a diligent preliminary assessment is undertaken to determine the facts of the matter.

In reality, the planning scheme amendment method is rarely used and generally reserved for applications that enjoy strong Council support. As a general rule, the Supreme Court method has become the preferred method for seeking changes to restrictive covenants. However, many applicants consider Supreme Court applications cost-prohibitive.

The planning permit application method, over recent years, had lost favour with applicants. This is primarily because of the arduous tests included within the Planning and Environment Act and how those tests have generally been applied by both Councils and VCAT.

Sec 60(5) of the Planning and Environment Act requires (inter alia):

(5) The responsible authority must not grant a permit which allows the removal or variation of a restriction referred to in subsection (4) unless it is satisfied that—

(a) the owner of any land benefited by the restriction (other than an owner who, before or after the making of the application for the permit but not more than three months before its making, has consented in writing to the grant of the permit) will be unlikely to suffer any detriment of any kind (including any perceived detriment) as a consequence of the removal or variation of the restriction

The Sec 60(5)(a) test, above, is colloquially known as the ‘perceived detriment test’ and is applied to planning permit applications that seek to remove or vary a covenant that was created/registered prior to June 25th, 1991. The Tribunal has, on numerous occasions, highlighted how difficult it is for permit applicants to meet this test.

In McFarlane v Greater Dandenong CC & Ors [2002] VCAT 696 (26 June 2002), the Tribunal noted:

- The stringency of paragraph (a) is perhaps not universally appreciated. It sets the bar extraordinarily high. The existence of any detriment of any kind (including any perceived detriment) is sufficient to defeat an application to vary a covenant.

In Dacre v Yarra Ranges SC [2015] VCAT 1453, Deputy President Dwyer summarised numerous previous cases and stated:

12a the Tribunal must be affirmatively satisfied that a covenant beneficiary will be unlikely to suffer any detriment of any kind if the variation or removal of the covenant is permitted.

12b it is not necessary for an affected person to assert or prove detriment because the Tribunal must be affirmatively satisfied of a negative, namely that it is unlikely that there will be detriment of any kind.

In Castles v Bayside CC [2004] VCAT 864 (11 May 2004), the Tribunal noted:

- This is a severe test in that any detriment, even a minor one more than counter-balance by positive considerations, will be sufficient to bar the granting of a permit.

In Giosis v Darebin CC (includes Summary)(Red Dot) [2013] VCAT 825 (16 May 2013), it was noted that:

- … the benefit of a restrictive covenant is a proprietary right that should not be lightly removed or interfered with.

…

- … In fact, the difference between the bars set by section 60(5) and the conventional planning test which requires a balancing of competing interests is akin to the difference between the high jump and the pole vault.

It is the difficulty in overcoming the ‘perceived detriment test’ that ensures very few planning permit applications, that seek to vary or remove single dwelling restrictive covenants, are successful.

However, in a more recent VCAT decision, Ahiska v Hume CC [2020] VCAT 194 (19 February 2020), Clause 1 Planning was successful in arguing that this bar had been met. In that appeal we sought to review Council’s refusal to grant a permit for the rewording of a covenant that would effectively result in the removal of a single dwelling restriction, from land within the City of Hume.

In Ahiska, despite its complexities, the Tribunal agreed that the perceived detriment test had been overcome. In ordering that Council must issue a planning permit for the removal of the single dwelling restriction the Tribunal noted:

- However, in this case, in light of my earlier comments as to detriment, I do not regard the absence of development plans as a fatal failure of this proposal. Whether there be two or more dwellings constructed, and irrespective of their configuration on the subject land, I am satisfied that the physical separation and lack of connectivity and visibility between the subject land and the benefitting land means that the owner of any benefitting land will be unlikely to suffer any detriment of any kind (including any perceived detriment) as a consequence of the variation of the restrictive covenant to remove the single dwelling restriction.

- Accordingly, I find that the Tribunal is not prohibited from granting the planning permit sought on the basis of the test contained in section 60(5) of the Act.

It is important for readers to note that the Tribunal was at pains to emphasise that its decision in Ahiska was based on the facts of this case and turned on the specific facts associated with the site’s location, its surrounding environment, proximity to beneficiaries and other characteristics unique to this application.

Although far from opening the floodgates, this decision does provide a little ray of hope for permit applicants (seeking to vary or remove covenants) who have legitimate cases, that warrant consideration via the planning permit application method. The bar associated with the ‘perceived detriment test’ remains very high – however, if the facts of your case stack up, the test can be met – even if you’re not Steve Hooker.

If readers required any further information relating to restrictive covenant removals, please do not hesitate to contact our office.

Seek Professional Advice Information contained in this publication should be considered as a reference only and is not a substitute for professional advice. No liability will be accepted for any loss incurred as a result of relying on the information contained in this publication. Seek professional advice in specific circumstances. Copyright If you would like to reproduce or use for your own purposes any part of this publication please contact enquiries@clause1.com.au for assistance. Clause1 Pty Ltd Phone: 03 9370 9599 Fax: 03 9370 9499 Email: enquiries@clause1.com.au Web: www.clause1.com.au